By Ellen Kuwana

Neuroscience for Kids Staff Writer

December 5, 2000

"I'm Going to Tickle You!"  When someone threatens

to tickle you and then comes toward you with fingers extended,

chances are you will burst out laughing, even if you haven't been tickled

yet. Martin Ingvar and his team of researchers at the Karolinska

Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, wanted to find out what your brain is

doing when this happens. Using a brain scan called functional magnetic

resonance imaging (fMRI), they compared brain images of what happens

during an actual tickle with those of an anticipated tickle. When someone threatens

to tickle you and then comes toward you with fingers extended,

chances are you will burst out laughing, even if you haven't been tickled

yet. Martin Ingvar and his team of researchers at the Karolinska

Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, wanted to find out what your brain is

doing when this happens. Using a brain scan called functional magnetic

resonance imaging (fMRI), they compared brain images of what happens

during an actual tickle with those of an anticipated tickle.

They found that an anticipated tickle activated the same areas

of the brain as a real tickle. The main areas that "lit up" were the

primary somatosensory cortex and secondary somatosensory

cortex indicating that the brain appears to be able to predict

what the sensation is going to be. Why might this be a good thing?

Visualizing possible outcomes might speed up response time to

potentially dangerous stimuli such as rapidly approaching objects and may

be important for avoiding or catching objects. They found that an anticipated tickle activated the same areas

of the brain as a real tickle. The main areas that "lit up" were the

primary somatosensory cortex and secondary somatosensory

cortex indicating that the brain appears to be able to predict

what the sensation is going to be. Why might this be a good thing?

Visualizing possible outcomes might speed up response time to

potentially dangerous stimuli such as rapidly approaching objects and may

be important for avoiding or catching objects.

Another Ticklish Question Have you wondered why you can't tickle

yourself? This is the question that Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, Daniel Wolpert

and Chris Frith researched at the Institute of Neurology, University

College London in England. They used fMRI to peer into the brains of

subjects while the people were tickling themselves or having their palms

tickled by someone else.

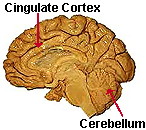

Their results suggest that you can't tickle yourself because

your brain predicts the tickle from information it already has about, say,

your fingers moving. Certain areas of the brain including the

secondary somatosensory cortex and the anterior

cingulate cortex are less active when you tickle yourself. The

people in the study also reported that they were much more "ticklish" when

another person tickled them than when they tickled themselves. Another

part of the brain, the cerebellum, also responded

differently depending on where the touch originated (from self or from

another person). The cerebellum controls balance and coordination, so it

might be involved in predicting what effect movement of one part of the

body has on other body parts. Their results suggest that you can't tickle yourself because

your brain predicts the tickle from information it already has about, say,

your fingers moving. Certain areas of the brain including the

secondary somatosensory cortex and the anterior

cingulate cortex are less active when you tickle yourself. The

people in the study also reported that they were much more "ticklish" when

another person tickled them than when they tickled themselves. Another

part of the brain, the cerebellum, also responded

differently depending on where the touch originated (from self or from

another person). The cerebellum controls balance and coordination, so it

might be involved in predicting what effect movement of one part of the

body has on other body parts.

Why Is This Research Important?

Anytime scientists learn something about how the brain works normally, it

sheds light on what might be happening when something goes wrong with the

brain. In this case, information about how the brain distinguishes

self-generated touch from touch generated externally could help unravel

one of the mysteries of schizophrenia.

Schizophrenics often have trouble distinguishing external events from

self-generated ones. As Dr. Firth, a co-worker of Dr. Blakemore, explains

it, there is a problem with self-monitoring. He gives an example

of a person with schizophrenia:

"My fingers pick

up the pen, but I don't control them. What they do has nothing to do with

me."

People with schizophrenia often believe

that they are being touched, even when no one is actually touching them.

Some people with schizophrenia "hear voices" (auditory hallucinations)

when in fact there is no one around.

To support this theory of a defect in self-monitoring in

schizophrenics, Frith and colleagues compared patients who had symptoms of

schizophrenia with patients who did not. The patients with no symptoms

reported that they were much more "ticklish" when another person tickled

them as compared with when they tickled themselves (this is consistent

with reports from the study above). Those who had experienced auditory

hallucinations and other symptoms of schizophrenia reported no difference in how ticklish they were -- they

experienced the same degree of tickishness whether another person tickled

them or when they tickled themselves! To support this theory of a defect in self-monitoring in

schizophrenics, Frith and colleagues compared patients who had symptoms of

schizophrenia with patients who did not. The patients with no symptoms

reported that they were much more "ticklish" when another person tickled

them as compared with when they tickled themselves (this is consistent

with reports from the study above). Those who had experienced auditory

hallucinations and other symptoms of schizophrenia reported no difference in how ticklish they were -- they

experienced the same degree of tickishness whether another person tickled

them or when they tickled themselves!

References: - Rostler, S., Tickling Your Fancy: How the Brain

Responds to Touch, on-line at www.brain.com, September, 12, 2000.

- Netting, J., Brain: Tickling Your Fancy, Nature, August 30,

2000.

- Blakemore, S-J., Wolpert, D. and Frith, C., Why Can't You Tickle

Yourself?, NeuroReport, 11:R11-16, 2000.

- Carlsson, K., Petrovic, P., Skar, S., Petersson, K.M. and Ingvar, M.,

Tickling Expectations: Neural Processing in Anticipation of a Sensory

Stimulus, Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12:691-703, 2000.

|

When someone threatens

to tickle you and then comes toward you with fingers extended,

chances are you will burst out laughing, even if you haven't been tickled

yet. Martin Ingvar and his team of researchers at the Karolinska

Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, wanted to find out what your brain is

doing when this happens. Using a brain scan called functional magnetic

resonance imaging (fMRI), they compared brain images of what happens

during an actual tickle with those of an anticipated tickle.

When someone threatens

to tickle you and then comes toward you with fingers extended,

chances are you will burst out laughing, even if you haven't been tickled

yet. Martin Ingvar and his team of researchers at the Karolinska

Institute in Stockholm, Sweden, wanted to find out what your brain is

doing when this happens. Using a brain scan called functional magnetic

resonance imaging (fMRI), they compared brain images of what happens

during an actual tickle with those of an anticipated tickle. ![[email]](./gif/menue.gif)

![[survey]](./gif/menusur.gif)

![[newsletter]](./gif/menunew.gif)

![[search]](./gif/menusea.gif)